I met her in Copacabana. She sat next to me at a café on Avenida Atlântica and ordered a juice with a husky voice. She was tall with toffee-coloured skin, long, black hair and a bosom that could smother Corcovado. She was wearing designer sunglasses perched upon a thin nose over protruding bee-stung lips. I can describe her appearance, but not her aura; on the beachfront with the highest concentration of gorgeous women and muscled men per square foot, she out-glamoured them all.

Emílio, my Brazilian friend, nudged me. “A travesti“, he pronounced with an air of seen-it-all-before.

I wasn’t so sure.

“Maybe post-op,” he continued.

“How can you tell?” I wondered.

“It’s obvious”, he said. “You only have to look at her. Hormones, silicones, collagen.”

I looked at her and there was nothing masculine about her mien. I stared for too long, our eyes locked and she smiled. Emílio waved her over to our table with that natural, instinctive Hi-I-want-to-talk-to-you Brazilian innocence. Her name was Alícia and it soon became clear that she regarded me - a gringo who spoke her language fluently - with the same exotic fascination I regarded her. We talked, and it was she who asked me out to a club that same night.

That night we partied together, Alícia and I, in Club W in Ipanema. I observed every nuance in her mannerisms. Like a good dancer, she came in comfortable low-heel shoes and a simple, short skirt; it was she, not her clothes that were flashy; and her vibrant, vivacious behaviour was supremely feminine. After several caipirinhas, I felt brave enough to broach the subject indirectly, as Emílio had advised me. I told her about a book I had been reading which described the story of Chevalier d’ Éon.

He was a French ambassador in eighteenth-century London whose gender was the subject of much speculation. And I mean real speculation, because there were bets made on whether she was a man or a woman. To the end he professed to be a man, but strangely, he refused to be subjected to a medical examination, and he was taken to court by a betting syndicate. After a bizarre trial, the jury decided (s)he was legally a woman and that (s)he should always dress and behave like one from then on.

My look must have been very questioning for she demurred immediately. “You’re wondering, too?” she asked.

Despite my long preamble, I was still embarrassed. “No, I think you’re a woman,” I said. “So beautiful you make both men and women jealous.”

It took her a long time to reply and when she did, she changed the subject. “So what was the end of your story?” she asked.

“She finished her days in a nunnery in France. On her deathbed, she was finally examined by two doctors. They determined that she was most definitely a man, though he’d been acting like a woman since the trial.”

Alícia laughed. “I love that”, she said. “That was great.” Then she turned to me: “You don’t want to wait until I die, do you?”

No, I didn’t, and I didn’t have to. That night, I did find out. But if it didn’t matter to me and if it didn’t matter to her, then it shouldn’t matter to you.

Unless you want to start taking bets…

[This article has also been published in the Sunday Times]

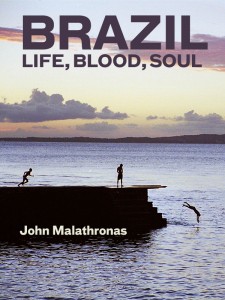

John Malathronas’s second edition of Brazil: Life, Blood, Soul is now available on Kindle.